I had to get to the start line within half an hour or I’d miss it. Stuck in this foreign town, I was lost between winding streets and strange houses, unable to find my race bag, or drop bags, or anything at all. Hadn’t I had some hiking poles somewhere? This was Logan, Utah. Wandering past me were people in robes wearing strange pointy hats and the only transport were gondolas propelled by magic only the strange pointy hat-people could work out in this Venice-like maze. There was no way I’d make it to the start line in time and… waking from a restless sleep I realized I was still in bed in Australia.

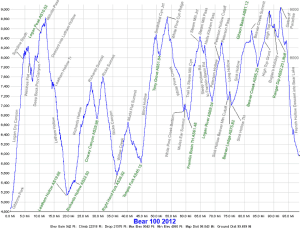

The frightful dreams I was having in the lead-up to my first 100 miler seemed to be getting more bizarre by the night. I’d never been so outright scared of a race. The first time I’d run a 100k seven years ago, I hadn’t trained for the distance and only swapped into it from the 42k version the day before the race, mainly out of curiosity. Finishing had been a complete surprise, so there had been no opportunity to be scared. This time, I felt like I was looking down into an abyss of the unknown, heading to a foreign land in potentially wild weather attempting a distance I couldn’t fathom. The Bear 100 Endurance Run from Logan in Utah to Fish Haven in Idaho runs through remote, mountainous terrain over 6,700 meters accumulated climb in weather conditions that, in past years, involved snow and ice or outright deluges.

Past race reports sounded gruesome and dangerous, with participants having dropped out after saying they had to slide down icy slopes on their butt. The course was said to be sparsely marked. I had no pacer, I had no crew, I knew nobody there. Lying in bed at night, I imagined getting lost in the dark, far from any road or mobile reception and freezing to death all alone. It was ridiculous, given that I’d be the first person to ever manage the feat of dying in this race, but it became increasingly difficult to get those fears under control. Perhaps I shouldn’t go at all. Perhaps I should just stay home.

Past race reports sounded gruesome and dangerous, with participants having dropped out after saying they had to slide down icy slopes on their butt. The course was said to be sparsely marked. I had no pacer, I had no crew, I knew nobody there. Lying in bed at night, I imagined getting lost in the dark, far from any road or mobile reception and freezing to death all alone. It was ridiculous, given that I’d be the first person to ever manage the feat of dying in this race, but it became increasingly difficult to get those fears under control. Perhaps I shouldn’t go at all. Perhaps I should just stay home.

I hate the cold, so I spent hours online researching ways to stay warm and read about rubbing chilly on your feet (ouch, chilly blisters?) and how to best run in deep snow, ultimately ordering a neck warmer, waterproof gloves and socks, and gore-tex running shoes. And in rare snow in Australia’s Blue Mountains, I did long runs clad in all my warm gear plus a fleece skirt fashioned from an old yellow jumper. I’d cut off the long sleeves and was wearing them on my calves as long gaiters.

“Record-breaking heat sets stage for the weekend” reported the Salt Lake Tribune on September 25, 2015, the day the Bear 100 started. This was to be an altogether different race. No snow, no ice, not even rain. I was outstandingly grateful even though I’d mainly brought Merino wool shirts to run in.

Registering at 5:30am, I asked a volunteer taking down my name: “Is that all?” “Sure,” he said with a grin. “That’s it. Now you just have to run 100 miles to Bear Lake.” Some last headlamp adjustments, and off we went, towards Mt Logan and a climb of over 1,100 meters up to the first checkpoint. I hadn’t brought a camera but I remember the sky that morning well as it slowly turned from dark to light, showcasing its beautiful colors across the mountains while we were climbing higher and higher. We were progressing in a long line and went slowly, but there is nothing wrong with taking it slow at the start of a race. Sooner or later, the trail would become wide enough to spread out a little.

I’d been enormously lucky. Just about a week before the start, my mother had spontaneously decided to travel from Germany to provide moral support and sample the beautiful hikes in the Wasatch area.

She was worried about driving in unknown territory and wouldn’t be crewing, but she’d helped me prepare, and had been at the start to see me off. I was incredibly grateful for that. My dad had been keen to find out everything he could about the Bear and was following online, and my sister and her kids had sent me an especially painted running t-shirt. For someone like me, who’s from a fractured family and had been in boarding school from age 14, that was pretty special. It was the first and only time they were all involved in a race I did, and I cherished the experience dearly.

And they weren’t the only ones helping out. Brendan Davies from UpCoaching had lent me various race packs for a week to help me decide which one to buy, and I was running in gaiters gifted by Lou Clifton, a very speedy running friend living in the Blue Mountains. German runner Manuel Hartl had even sent me a parcel to Utah full of beer-flavored energy gels and other running provisions.

And then there was the Logan running community, which must be one of the most welcoming in the world. In reply to a post in their facebook group upon arrival in the U.S., I’d immediately received several messages and an invitation by Scot Weaver to a group pasta dinner at his and his wife’s place.

Scot, one of the friendliest people you’ll ever meet, got me in touch with Joe Furse, a highly talented runner in his 20s who’d run the Top of Utah Marathon in a blistering time of 2:38. I’d warned I’d be rather slow, but Joe immediately offered to pace me, and Joe’s wife Jenny offered to drive him at some nightly hour to the meeting spot. I was also fortunate to meet Chuck and Babette Burtis, both very fast runners in their 50s who had qualified for the 2016 Boston Marathon. Hearing Joe and me talk about the Bear, Chuck also offered his help. Some days later, Chuck said he’d also roped his brother in law Wade McFarland into pacing me and they’d organize the distances amongst each other once.

Instead of none, I now had three pacers, and all of them locals who knew the course. I was blown away by their generosity and readiness to spend so much of their weekend helping a complete stranger. Instead of feeling blank fear, I now couldn’t wait to spend hours in the company of such lovely people traversing this beautiful part of the world. People can make all the difference. Not to say I wasn’t still scared, but I felt a whole lot better about my endeavor.

Once we were over the first massive climb, I took the chance to speed up a little to make my next split at the Leatham Hollow Aid station in the Valley.

The trail had widened into a dirt road and I spent some time chatting with Charles Spelina, who’d come over from New York and was also doing his first 100 miler here.

The race is held in fall to let runner enjoy the Indian Summer with its vivid colors that time of year, and deep red, orange and yellow of the trees lined our path. Running was still easy as the air hadn’t warmed up yet, but by the time I reached the second checkpoint, the heat was definitely up. It was well over 30C, and some later said temperatures were pushing 40C in the valley. I don’t know what the exact temperature was, but the next fairly flat stretch through the valley to the third checkpoint felt like running in an oven.

At Richards Hollow checkpoint a volunteer had the brilliant idea of putting ice in my cap and in my water bladder, and, boy, did that help. The trail now led us back up again along some shady trails, past numerous cows, but no bears, which prompted someone to remark that this race should rather be called The Cow 100.

A runner greeted me by name, leaving me confused for a moment, until I realized it was Charles, who’d changed into a different-colored shirt. This was a trick he’d stick with through the entire race, and I somehow never learned that a familiar looking guy in an unfamiliar outfit calling out my name would be Charles.

We now headed onto open road where the running was easier but the sun was beating down relentlessly. I focused on drinking much more than usual, finishing off 2.5 liters between aid stations and taking 4 salt capsules an hour. My fingers had started to swell when taking less salt. Still, I preferred the heat over icy slopes. Having to negotiate these trails in ice, mud and rain would have been incredibly tough.

I arrived at checkpoint 4 Cowley Canyon in good spirits, went through my drop bag and left with some new fuel and another 2.5 liters of water in my pack. At over 30C for most of the day, it seemed wise to run smart and preserve energy, taking any time necessary to drink and eat enough. I still had a long way to go. Also, I was wearing black merino wool. I can’t quite remember why, it’s just what I always run it, because it works well in warmth and cold, and doesn’t stink. But now I wished I’d taken something light and white instead. Different to Charles, I hadn’t left any new shirts at aid stations.

I’d fallen behind my splits in the heat but was still feeling quite fresh in my legs. Conservatively walking all the uphills, I had no problems running the long downhills and most flats, and made up good time on those stretches. There also were no issues with blisters after lathering my feet with Bodyglide in the mornings and evenings for two days before the race, and wearing toe socks to keep chafing to a minimum. Nerves had kept me awake for most of the night though, and I’d had only one or two hours of sleep. I wasn’t feeling it yet, but I was going to come to curse those sleepless hours later on.

Finally, the path turned off into a trail down the mountainside with much of it meandering in the shade. The large quantities of water and salt I’d consumed were paying off and I was fresh enough to run the whole way down, not being far off check point 5 at Right Hand Fork now. Not having a crew does cost time, and I was amazed at how many minutes can get lost when looking for drop bags, going through provisions, running to the toilet, and filling up a pack. I was definitely behind schedule and could only hope that the tracking system was working and my first pacers knew I was running late.

I’d hoped to make it to Tony Grove by dark, but it was now clear that night would fall long before that. Pacers were allowed from Right Hand Fork at checkpoint 5, but I’d agreed to meet Chuck at checkpoint 7 at Tony Grove. Keen to get as much done as I could in the fading light, I didn’t waste much time at checkpoint 6, Temple Fork, which wasn’t even halfway through the race yet at 73k. Other runners passed me with their pacers and I keenly wished I’d have company, too.

Suddenly, I heard someone calling after me. It was Chuck! He’d tracked my progress online and knew I wouldn’t make it to Tony Grove before nightfall, so he and Wade had driven to Temple Fork. On hearing that they’d only just missed me, Chuck had jumped into his runners and headed out after me. I was so happy to see him.

I was tired but with Chuck’s company and cheer, the next climbs weren’t so hard anymore and soon we were running again on the flats and downhills. At one point, we passed a runner standing somewhat slumped next to the trail. I checked whether he was okay and had enough salt, and heard he was struggling with cramps, a problem I’d luckily avoided with the high water and salt intake I’d stuck to all day. He said he’d run out of salt, so I gave him enough of my capsules to last him to the next station where he could pick up more.

It was a beautiful night with a near-full moon and for much of the way we didn’t need to switch on our lights. The air was still mild after the heat and felt so soft and refreshing, and the meadows and trails ahead of us looked so inviting, that I’d never enjoyed running at night this much. I felt I could have just continued forever then.

“Hey Nicky!” I heard as we passed a runner and his pacer. “Hi… good work!” I called back, pondering who could know my name when I didn’t know his. Of course, it was Charles again in a new shirt.

Running into Tony Grove, we were greeted by Wade, who checked if we needed anything before he would take over pacing at Franklin Trailhead. I don’t remember the next stretch as being hard, and was surprised how much energy I had still left in my legs, running fairly easily on downhill and flats after a distance I’d in the past found much harder. I finished these first roughly 100k to check point 9 quicker than I’d finished the NorthFace 100k in the Blue Mountains in 2014, despite this stretch at the Bear probably involving more climbing and being significantly hotter. It pays to drink plenty, I noted. I usually don’t drink enough.

Sitting down to change shoes and socks at Franklin Trailhead, Chuck and Wade provided me with the kindest care. They helped me out of my shoes, and even gave my dusty feet a good clean with some wet wipes before helping me into fresh socks and a different pair of shoes. Lori Bowcutt, whom I’d also met at Scot’s group dinner, was volunteering and it was wonderful to recognize another face. She kindly got me some soup and encouraged me on.

I was also very glad I’d been able to catch up with Badwater finisher and experienced ultra runner Tammy Massie in Salt Lake City just before the race. She’d insisted I change shoes at least once, so I’d left some at this checkpoint. And sure enough, just the last few kilometers before this aid station, I’d developed a hot spot on one foot that would have turned into a blister without a shoe change. Afterwards, I had no more troubles and amazingly didn’t develop a single blister the entire race.

Wade expressed amazement at my good mood after 100k, but who could be grumpy being so lucky. I’d known no one on arrival, but was now surrounded and supported by wonderful people who were helping me achieve this dream of finishing my first 100 miler in this amazing place.

To highlight how kind and enormously patient my pacers were, I should add that Chuck, 58, ran the St. George Marathon in a time of 3:07:53 a week after pacing me, and that Wade holds the Top of Utah marathon age group record both for the ages 50-54 and 55-59 with a time of 2:50:35 and 2:58:58 respectively. Also, the way runners treated each other in this race was always encouraging and kind and you could just feel that the event was run by people who truly care about the running community.

When our time together was up after this aid station, I was sad to see Chuck go and missed him like an old friend. But I had Wade with me now to keep me company and help me find the way, and it was urgently needed.

After leaving Franklin Trailhead, my energy level had taken a sudden dive. I was so slow. We were climbing a seemingly endless way up and once the trail ran flat again, I no longer felt like running. Wade suggested moving faster. I shuffled unenthusiastically behind him. Somehow my brain had now realized that I’d never gone this far before, and the old “hey, this is crazy, what are you doing, stop this” was back. I hardly made it up each hill.

I wasn’t worried I’d stop, but wondered where all that energy I’d still had just a few kilometers ago had suddenly gone. Some runners overtook us but there were also some who were doing worse. One runner was retching while holding onto a tree as we passed, with her pacer supporting her. I was also becoming less and less interested in food, but at least I hadn’t vomited yet.

It’s always great to make it to an aid station, but number 9 at Logan River was dangerous, in the sense that there was an all-too-inviting fire burning. It felt like a home I had no wish to leave. The night had been kind and mild, but it wasn’t exactly warm, and exhaustion made it feel colder. I could no longer eat while moving, but managed to eat soup sitting down. So I saw down and ate two soups. All I wanted was stay, and never move again.

After over a quarter of an hour rest I thought my stomach would be well enough to eat a grilled cheese sandwich on the way out. One bite standing up and I felt so sick I quickly spit out the bite and threw the rest into the bin. My body had firmly decided that it couldn’t focus on eating and moving at the same time.

Soon we came to a creek with a couple of logs across. For a tired runner, there were definite opportunities to fall in, and this wasn’t a good time to get wet. So I took the less graceful option of crawling across the log on hands and feet until only a few balanced steps from stone to stone remained. Success! Not even my feet had gotten wet, so after a quick breath of relief, we were off again.

In view of my recent decline, I had thought it impossible to slow down any further without standing still, but you surprise yourself in ultras. The low food intake over the past hours was having an impact, and the steep hills felt like the Alps. Other runners I’d overtaken before Franklin Trailhead were now passing me and I had no idea how anyone could move as fast as them.

“Hey Nicky!” one stranger called out as he passed me. I was too tired to wonder, but it must have been Charles in a new shirt. I regretted not taking more than the one piece of hard candy I’d grabbed at the last station, as that seemed to be the only thing my stomach was still interested in. Going only on ginger ale now, I stumbled after Wade, who tried to encourage me to run whenever the trail was going downhill. I was so slow that he often got out of sight and would wait for me down the track. He told me about the local wildlife and that there’d surely be mountain lions in the trees watching us, we just couldn’t see them. I couldn’t care less. Don’t they say you shouldn’t run if you see a mountain lion? Even more reason to walk.

With great delay, we finally made it to Beaver Lodge at about half past six in the morning where Joe and Jenny were waiting for us. I’d been on my legs for over 24 hours now and we were at roughly 122k. They hadn’t been waiting too long, they said. Joe was a good predictor of speed and looking at my earlier progress, he knew I’d be arriving later than planned.

I think he was keen to get going, but I was trying to consume calories sitting down. I really can’t praise Joe highly enough. He’d never run the Bear as a race himself but had paced numerous times – usually people who have a chance at winning the race. A runner he’d paced in 2015 finished fourth overall. With me, pacing would mean hiking. Slowly. We jogged a little to start, but it didn’t last long. I wanted to take the safe route to finishing. I no longer cared that I’d be far from my original target of under 30 hours. I just wanted to be absolutely sure that I didn’t injure myself or did anything else that would keep me from finishing. And at this point, I wasn’t quite sure whether my legs mightn’t just suddenly give way if I wasn’t careful.

Of course, walking takes a lot longer than running, and thinking that we still had more than 35k to go at this speed seemed insane. I felt incredibly tired and had lost all recollection of why I was doing this in the first place. Why was anybody doing this? Who were these people?

But there was Joe, spending his Sunday sharing the trail with me, and there were all sorts of other people hobbling along, so sensible or not, this appeared to be the thing to do. I was also using this race to raise money for an asylum seeker center in Australia that provides food and health services, as well as language and jobs skills training, and this provided further motivation. Joe stayed close, mostly beside me or just ahead, and was indispensably patient company over all those kilometers.

My short-term memory wasn’t no longer working and I fortunately forgot most of the climbs. When Joe told me about an upcoming climb, saying it wouldn’t be quite as bad as the last one, I couldn’t remember the last one. Somewhere we crossed into Idaho and were soon close to the 11th aid station at 130k. We wasted less than three minutes at Gibson Basin aid station and hiked out onto a long straight fire trail.

It was mid-morning now and I had been awake for too long. My mind was running off track. Sometimes I forgot we were in a race and thought we were out for a morning stroll. At other times, the most burning question on my mind was whether Joe had ever ridden on a deer.

As soon as I’d banished that deer-riding quandary from my mind, it turned its focus to frog liver pâté. But do frogs even have livers? The lack of answers drove me insane. However, I stopped short from mentioning any of this to Joe. ‘You’re slow, and Joe might be bored, but look how patient he is,’ I thought. ‘If you ask him about deer-riding and frog livers, he might get worried and run away.’ With Joe by my side, I knew I’d make it through this second day somehow, so I wanted to appear as normal as possible to him. Frog liver pâté might just ruin it, I thought.

At about 10am, we arrived at the second last aid station, Beaver Creek at about 137k. There were soggy pancakes and fried eggs, which were divine. And I could actually eat them, which was even better.

The toilet options were a bucket in a tent or some bushes. A volunteer recommended the bushes over the bucket. I took her advice. Being that tired, the classification of: “am I sufficiently out of sight” somewhat changes. The bushes weren’t very thick but they were in a kind of dip, and the only question that really mattered now wasn’t “am I out of sight” but rather “is my butt out of sight”. If the answer was yes, it was good enough. Not that anyone cared at this point anyway.

Before heading off again, I dug the race t-shirt from my niece and nephew out of my drop bag, and also found an encouraging card from my mom. I was tired, but I happy now, that sleepless-and-having-run-a-long-way kind of happy.

At my speed, it took nearly three hours to get to the last aid station at 148k. The sun was high in the sky, but I’d become less diligent with my water refills to keep the pack lighter, and had run out a while ago. I was glad to fill up. One last steep climb up to the highest point in the race at 2,756 meters and then, finally, we were over the last big hill. Now it was less than 10k to the finish, and most of it was steeply down.

Suddenly I found my legs again. Only 10k! Jogging again, we ran through colorful autumn leafs, blown about by a cheerful breeze. The sight of Bear Lake, stretching out below in a deep blue, accompanied us on the entire way down. With the finish line so near, we were overtaking people and I was keen to keep moving. The track was washed out and steep with loose gravel where I had to catch myself a few times, but we were moving. Now Joe was certain we’d make it in under 34 hours. Far from my original goal, but long ahead of the 36 hour cut off. I would finish.

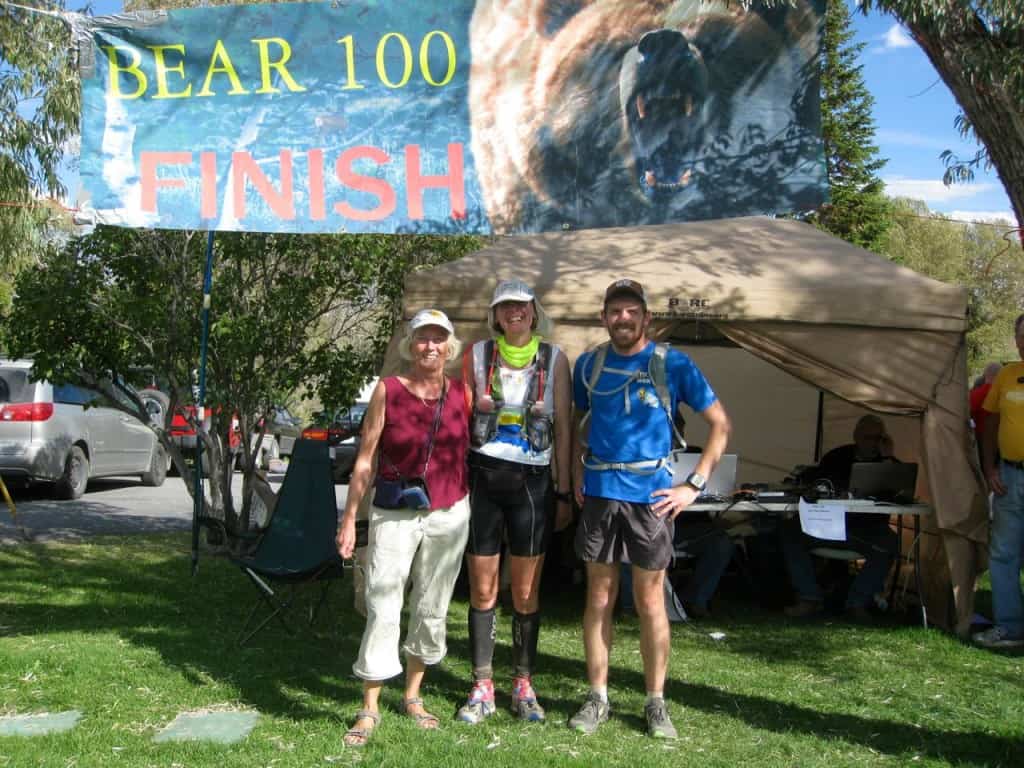

As we came off the hill and turned onto an asphalt road, my mum came towards us cheering and running with us. I was amazed how well she kept up, because in my mind we were going fast and I was giving it my all. Then I realized how slowly we were jogging. It no longer mattered. Jog we did, with big smiles, through Fish Haven and into the finish.

I can’t remember much more than being happy and grateful for all the help I’d received, for my pacers, my mom, the company of all the other runners, the organizers and volunteers, and for being allowed to successfully complete such an experience.

I also remember thinking briefly that most things that seem difficult or even insurmountable on other days, probably weren’t all that difficult in reality. All seemed doable right now. Mom remarked how everybody she’d watched coming in had been smiling, and she wasn’t sure how that was possible after 100 Miles.

And then, after getting my buckle and a hug from co-race director Errol “Rocket” Jones, cheering on other finishers, thanking Joe and giving him a couple of things as a memory of the race, while resolving to mail the little gifts I had for Chuck and Wade the day after, I stretched out in a sleeping bag on the grass and immediately fell asleep, right among all the commotion.