“No peein’ off the porch” is the sign that greets me as I wait on Craig Thornley’s deck.

He is in the kitchen to make tea and one of his cats is keeping an eye on me from under a wooden bench. What do Western States runners get up to on their race director’s porch?

Once he joins me with two mugs, he tells me it was just one guy, but he was a repeat offender. Some house rules might be inevitable, given how full his and his wife Laurie’s house can get come June. The location is no accident – the race director lives just a mile from the Western States 100 Mile Endurance Run finish line.

Listen to the full interview with Western States Race Director Craig Thornley:

This week, thousands of runners around the world enter the lottery in the hope of scoring a spot in this iconic race from Squaw Valley to Auburn, California. Numbers are capped at less than 400 runners, due to permits.

The organizers want to balance being an elite event that grants some top athletes automatic entry with being inclusive by giving also slower runners who have managed to qualify a chance to participate. Either way, those chances are slim and stand at less than 5% at first try. The most consecutive years you qualify and enter, the better the odds.

WS has come a long way in four decades. Originally a 100-mile race for horses called the Tevis Cup, a man called Gordy Ainsleigh one day decided to run it, and finished in under 24 hours.

“He obviously had something in his head that not too many of us were, at least, able to show that we had it. So he decides to run,” Craig Thornlesays.

After that first finish in 1974, the race doctor thought it was a once-in-a-lifetime feat that no one would ever duplicate.

“It was just so far out there to think of running in these kind of temperatures and this terrain, the canyons are just not very friendly, and he just started this crazy sport. It wasn’t that he started ultrarunning, but it was covering 100 miles in this type of terrain, ” Craig says.

By now, thousands have finished WS and many thousands more want to run it.

The training weekends, such as the Memorial weekend I took part in, are one way to see much of the course without winning the race lottery. Anyone can take part, and volunteers often include highly accomplished runners with a long WS history, such as Tim Twietmeyer or Ann Trason.

Craig sees runners off in the morning and greet everyone with a big smile and some hugs at the finish line each day.

The race director has grown up with this race. When Craig was a teenager, it found him in the form of an exhausted runner tumbling out of the woodwork as he and his brother were out camping.

The runner wanted to know where the aid station was. The brothers had no idea what he was talking about, but they never forgot the look in his eyes.

“Not blank, but there’s definitely a whole lot going on and we just knew that we have to experience whatever they are experiencing. You could read a lot into those eyes,” Craig said.

After working the Dusty Corners aid station for 10 years, Craig ran the race for the first time in 2001 and finished, a feat he has pulled of seven times since, always in under 24 hours.

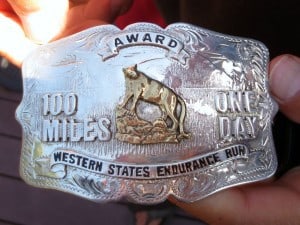

Finishing in one day earns runners a highly sought-after silver belt buckle. These buckles are custom-made from sterling silver and valued at USD 355 – nearly the race entry fee.

The belt buckles are another legacy from the Tevis Cup, originally meant for riders. The makers from Comstock Heritage aren’t runners themselves, but have a lot of appreciation for what the buckle means to people.

“They are totally engaged, they are excited that they get to make the buckle that so many people want to earn.”

“It’s not just that it’s a 355 dollar buckle, but it’s what that buckle represents, that whole effort, commitment, not just on race day alone but getting to the race and preparing, and all the sacrifices. It’s symbolic of so much more than just a finishing time.” Watch how the buckle is made.

It’s not the first race Craig Thornley has been directing, but it’s certainly one on a completely new scale. His professional background is in IT, but on the side he’d already set up the Waldo 100k Trail Run in Oregon.

“I started developing Waldo and it became a really well-respected race, it was a national championship,” he says.

“I got to implement my ideas of what I think a race should be like, treating every runner equally, first class service at aid stations where the volunteers are very knowledgeable. […] I got to use it as kind of a playground, as a learning tool.”

Added to his race organizing experience, Craig was also a national sky patroller for years, and stewarded 16 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail. So when the WS role came up, he had no trouble getting an interview. He did have trouble getting TO the interview, though.

Having committed to helping champion runner and friend Meghan Arbogast race the day before, he’d booked the earliest morning flight to make it in time.

It ended up being an epic day of flight delays, missed connection flights, rebookings, and finally a way-too-helpful rental car assistant hell-bent on selling him everything he didn’t need, ultimately leaving him chasing down the highway with no time to lose.

And then there was the problem of not usually using deodorant. We all know what happens when you’re under a lot of stress and there’s no deodorant around. Not good.

“The interview of my life and I smell so bad!” he laughs.

He was driving so fast that he made up enough minutes to storm into a petrol station and get some deodorant, and – smelling beautifully – got the job.

So now that he’s held the position for three years, where does he want to take the race?

“I definitely want to see us involved in the international scene. We are already making contributions by being involved in Ultra-Trail World Tour and the International Trail Running Association. I want to see the race continue to be relevant on the competitive scene in the world, attracting the top 100-mile runners of the world,” Craig Thornley says.

Craig is conscious of the fact that WS has less than 400 runners each year, while races like the UTMB series have thousands.

He believes the event’s relevance could decline if they don’t stay on top of things, cooperating with and learning from other races around the world.

“I want to make sure we continue to lead the sport and have the best practices in everything.”

The race also wants to continue evolving its medical research. Changes include moving away from overusing IVs to combat hyponatremia (abnormally low blood sodium levels), as it has been found that the risks often outweigh the benefits of this practice, and most runners will recover without infusions, Craig says.

“When we do get a case of hyponatremia we know now that we can give people hypertonic saline, which is three times the normal saline of your body. If you’re not hyponatremic it won’t hurt you, and if you are, it will help you equalise sodium in your blood, in your body, much faster.”

Continuing to attract the best of the sport is important, but WS also continues to be committed to welcoming runners from all walks of life and making sure everyone is treated equally special on race day.

“Every person who comes to WS, whether you are 30 hours or whether you are 14 hours, has an experience that will be unmatched. It will be a memorable day of your life, you will not forget your experience at WS.”

This year, the last finisher was 70-year old Gunhild Swanson, who made it with seconds to spare before the 30-hour cut-off, becoming the oldest woman to ever have finished Western States.

She ran the last mile accompanied by family, friends and overall winner Rob Krar, who cheered her on wearing flip flops after having finished his own race in 14:48:59 – a beautiful show of how much camaraderie there is in the sport.

1 thought on “No peein’ – Craig Thornley on Western States, and porch rules”

Comments are closed.