What I remember most about dragging myself up steep, muddy and slippery mountain trails during the 2014 Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc CCC is a sense of embarrassment about hating 90% of it. It was raining from afternoon onwards and come nighttime, the trails looked as you would expect after thousands of people have trodden on wet ground ahead of you.

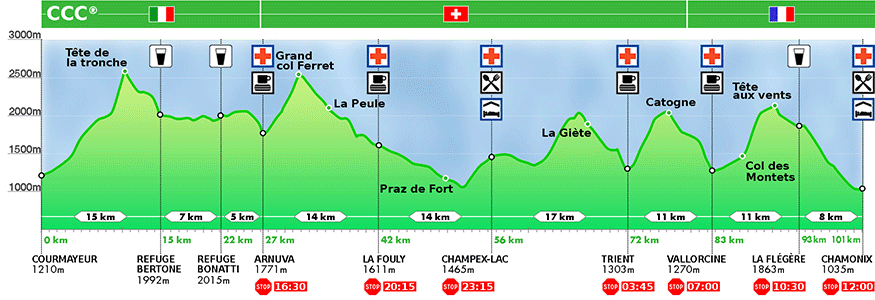

In some places, streams had diverted onto trails, turning them into creeks. Sometimes the mud was so deep that you had to worry about losing a shoe in it and some downhills were so slippery that moving forward reminded of an unstable skiing experience. And there’s a reason you have to qualify for this race — the 101k distance from Courmayeur to Chamonix includes 6100m accumulated positive altitude change.

But this was part of what I’d signed up for – and the UTMB series is a world-famous event around Mont Blanc through three countries and heart-stopping scenery — winning the lottery to take part is a privilege, and whinging about it seems out of place. Why would I not enjoy it and why keep going if it’s no fun?

Mainly, neither my body nor my head were up for it.

Mainly, neither my body nor my head were up for it.

I’d rolled my ankle badly three weeks earlier and was wearing an ankle brace, had trained a pitiful average of about 20k a week for the three months since the NorthFace100, had just gone through a relationship breakup, moved house, renovated while working, and felt completely wiped out.

If it had been any other race, I would have cancelled. But it was the UTMB series CCC, which you need to qualify for and then win the lottery to take part.

And — most of all — my mum had decided to support me for the first time at a race. I was immensely grateful for this, and a little scared, unsure of whether her presence would make running easier or harder. I hadn’t lived with her since age 13 and feeling supported wasn’t a sensation I naturally associated with her.

I crossed the start line with nearly 2,000 runners ahead of me and there wasn’t much running for the first two hours, just a long line of people as far as the eye could see.

I crossed the start line with nearly 2,000 runners ahead of me and there wasn’t much running for the first two hours, just a long line of people as far as the eye could see.

We shuffled our way up mountain sides like a determined procession of ants. At one point, as we were filing onto a single track from a wider road, there was complete standstill for at least 20 minutes.

The race felt commercial compared to the smaller trail races I’d come to love. There was a lot of expensive new gear flashing about, but I saw little of the social fun and camaraderie normally shared at trail runs.

I even saw someone going out of his way to hinder another runner from passing, several times, even though we were at the back of the pack. If that guy blocking the way was doing so because he wanted to win, he really needed to hurry up.

The views were beautiful but I felt frustrated and my mind wasn’t in a good place. The breakup saga was running loops in my head, my ankle hurt with every uneven step, and come nighttime, I was feeling truly miserable.

With the lack of normal camaraderie on the trail, all I wanted was to catch up with my mum at Champex-Lac aid station, get a hug and some supplies and warm clothes from her to replace the ones that were now wet despite the rain jacket.

When I finally arrived and searched high and low for her, I received a text learning that her bus was running too late for her to get there in time.

The exhaustion of ultra running can make one emotionally vulnerable and bring up a range of unprocessed old feelings, and as I drudged on through the rain and mud feeling cold in my wet gear, I was certain that my mother, who was spending her day chasing after me in a bus, didn’t care enough about me to be there when I needed her. Highly embarrassing in hindsight.

At some stage though I made my peace with the situation and stopped thinking that if this event wasn’t fun like other runs I’d done, or if the interactions and support I wished for weren’t there, it was going wrong.

Each race has its own challenges and all I had to do was to figure out how, not whether, to deal with those particular ones at hand. They say running while tired is good training for the next race. Moving forward while tired, sad and frustrated is also really good training, especially mentally.

As I came into Trient aid station, my mum shrieked with excitement on seeing me, being glad to have finally caught me. We gave each other a big hug and were so happy that a man standing next to us just watched us with a big smile on his face.

She was as bright as she could be at 2am. I was worried about her and told her to head back and get some sleep.

“I’ll be okay, I feel good,” my 68-year-old mother said in an upbeat mood.

And indeed, hours later, I saw her again at Vallorcine aid station, having stayed up all night traveling about to support me, with only small naps while waiting. That’s pretty impressive.

By sunrise, there was only one big climb and descend left to tackle and I was in awe of the mountain tops towering over the morning mist as if they were floating on a white lake.

I thought of mum waiting at the finish, and my friend Manuel Hartl who’d driven down from Frankfurt to meet me after the race. Things were looking up. Once I was over the last climb, I ran all the way to Chamonix in happy anticipation of seeing them.

At 25:33:38, I made it with less than an hour to spare before the cut-off. But I’d been lucky to avoid further injury in difficult and slippery terrain and persisted despite feeling down.

Also, the experience and shared time in Chamonix around the race strengthened the bond between my mum and me, at least for a while, and that’s very precious.

At the official post-race dinner, she looked incredibly pleased among all the runners and developed an interest in the sport. Soon she told me I should be doing more front-foot running like Scott Jurek.